Harry McIntyre

12 Nov 1930 - 15 August 1994

This page is in memory of my dad. He wrote this in 1994. It has nothing to do with Celtic, but he would have loved the fact that people around the world can now read his memoirs. These are his own words. Hope you enjoy it.

Foreword

Harry McIntyre (1st February 1994)

Some seven or eight years ago, I decided to research my family tree, and as I uncovered great great grandparents, I realised that I knew nothing about them, apart from the few sketchy details. I thought that was a pity that they hadn't the forethought to jot down a brief synopsis of their lives, e.g. what kind of house did they live in, what their occupations were, the wages they earned, how they met their spouses etc. (perhaps they couldn't read or write) to pass on down the generations, for such as I, who would have found it most interesting.

To this end, I am going to try and write about the kind of life I've had. I have no writing or grammatical skills and will probably deviate a lot.

If this journal survives, some McIntyre or whatever their names may be, may find it interesting in the future. I make no apologies for the expletives that will punctuate my writing. How is it possible to write about people, or yourself, if you don't use the language that they used?

When I am dead and in my grave

And all my bones are rotten

This little book will tell my name

When I am quite forgotten.

1930s

I was born at 133 Grovepark St, Maryhill Glasgow , NW on the 12th November 1930. My parents were Henry McIntyre and Sarah McIntyre (nee Scott.) Home for me was a third floor room and kitchen in a slum tenement. The kitchen was where the family slept, cooked and washed. It had a bed recess or hole in the wall bed, where I was born and where my parents slept. It comprised of a spring mattress sitting on bed boards. It could be shut off from view by a pair of curtains. I also slept in this bed with my parents until I was maybe 7 or 8 years old. (No wonder I was their last child!)

There was also a black leaded range, which had a black cast iron kettle sitting alongside the fire to give us hot water. The kettle had a couple of marbles or bools which started to rattle when the water level dropped, telling one to refill it. Such technology! There was a small gas ring which sat on the range where the meals were cooked. The oven was heated from the fire. The sink was of black cast iron. It only had a cold-water tap and this was where the family washed and where mother washed small items of clothing with the aid of a scrubbing board, which was made of a wooden surround and corrugated zinc. I think that they cost sixpence from Woolworths. I saw one recently in an antiques fair and it was on sale for £15!

The sink was also used by the family to pee in during the night, rather than go out to the WC or the cludgie as it was called, which was outside on the half landing. Ours was shared with the family next door. It was a terrible place. There was no glass in the window, no seat on the pan. There was never any toilet paper in it. Small squares of newspaper with a piece of string through them hung on a nail on the wall. The newspaper made your bum black (how did I know!) The first words I ever strung together probably were 'There's somebody in' as a neighbour tried to get into the cludgie. I remember thinking that if I was rich, I would have a toilet with a velvet seat on the pan, a small stove to make a cup of tea and a magazine rack for my comics, so that I could spend a pleasant half an hour in there. The kitchen also had a wooden table, which got scrubbed faithfully. I don’t remember seeing a table cover on it. It was usually covered with a couple of pages of the Evening Times. I think this was where I learned to read at an early age. With no electricity in the house, lighting was from a gaslight, which had an inverted mantle, which was so fragile that a bluebottle landing on it would put a hole in it, reducing the light given out. Because we had no electricity in the house, the radio, or wireless as it was called, ran off two batteries. One was large, one was small. Also an accumulator was required, which contained a lead cell and acid. This had to be recharged every few days by electricity. Having none in the house, we would take ours to Mrs. Wishart's newspaper shop in Hopehill Rd, where she charged them for people like us. I think she charged one penny for an overnight charge. Popular programmes in the thirties were ‘In the town tonight’ ‘Band Wagon’ ‘ Into the Battle’ and ‘Hippodrome.’

The kitchen had two pulleys, where mother hung her washing to dry. One had to go about the kitchen with head bowed, to avoid getting slapped in the gub by the wet washing. The kitchen was wallpapered three quarters of the way up, with a one-inch border. The remainder of the wall to the ceiling had frieze paper, which got whitewashed. There was also a shelf which ran the length of the wall across from the fireplace. This was used to store the best crockery (if you had any that is.) Our next-door neighbour was very posh. They used to put sticking plasters around the jam jars, so that you didn’t burn your fingers when you were drinking your tea! Back to the shelf, we used to have pewter and delf dishes laid out in descending order of size. What the hell they were for, I'll never know. There were also the inevitable brass jam pan and kettle. I never saw them being used either. Also on the shelf was a paraffin lamp (which had belonged to my grandmother,) which was used if one didn’t have a penny for the gas meter, which was also on the shelf. My sister Annie still has the lamp, which now must be well over 100 years old. The gas meter would get emptied every so often. The gasman would lay out the pennies in twelve’s (One old shilling) and mother would get two or three shillings back as rebate. You were always sure to get a penny from your mammy for sweeties after the gasman left. You could get quite a lot for a penny in those days. Four dainty caramels, two macaroon bars, two ice cream pokey hats etc. The gasman was sometimes asked to call again by some women, when their husbands would be out, incase he commandeered the rebate to buy drink.

The lobby, which connected the kitchen with the bedroom, was unlit and contained the coalbunker, the clothes poles and a rack for hanging up coats. The bedroom had two double beds and a hole in the wall bed. This was a posh one. It had a door on it. The bed that I later slept in was hoatching with fleas and bed bugs. I would wake up in the morning to see what nocturnal damage they had done to my body. I would be covered in bites. I became a dab hand at killing them between my thumbnails. The bugs gave off a terrible smell when they were burst. I didn’t really think anything of the bed being hoatching. I suppose that I thought that everyone else’s bed were the same. I would like to have seen my mattress being burnt. It would have gone off like Chinese crackers, as the fleas and bugs exploded!

There were eight families living up our close. The McKillop’s, McLaughlin’s, Straiton’s and Morrison’s. I can’t remember the names of the others. My parent previously lived in a ‘single end’ in the close and when my mother’s mother died, they moved up to the top flat to her house. My mother took care of her brothers and sisters. God knows where they all stayed. There were thirteen of them! One of the pastimes for the people in the street was to ‘hing’ This was kneeling on a on a chair, looking out of the windows, leaning on a cushion and shouting conversations to each other. This would go on until the early hours of the morning in the summer. I remember hinging one night, listening to a fight in a house across the street, along with the other neighbour's. When it ended, the lady, who was English, came out to apologise to everyone for disturbing them, saying ‘I’m very sorry for the disturbance you shower of nosey bastards’ I nearly fell out of the window laughing!

This lady kept a house of ill repute, or a knocking shop as we called it. There was a constant stream of men who would go in. they must have been hard pushed, for she was no oil painting. If beauty is skin deep, she was born inside out. One night when I was hinging, two detectives came creeping down the street and tried to peer into her window, which was on the ground floor. When they heard me laughing, they looked up to me and said ‘Get tae fuck inside that windae ya wee cunt.’ In those days, there used to be a lot of vendors who came round the streets with their horses and carts. Very few vehicles in those days. The coalmen all had their unique calls. Instead of ‘coal’ it would sound something like ‘awall.’ In those days when money was scarce, some ladies would pay the coalman ‘in kind’ behind the door, or give him a table ender. I heard one coalman who was heard to shout, ‘coal for money’ as he hung weakly onto a lamppost! There would also be a fish cart that came round selling ‘Loch Fyne herring 10 a penny.’ He would have to sell 2400 to make a pound. I don’t know how many he would have to sell to make a living, and feed and stable his horse. There was also a ‘soor milk cart’ that came round the streets. The milk would be in large churns and people would go to him with jugs. I could never stand the stuff.

There was a stable across the road from us where the coalmen etc would stable their horses. Some of the lads around the street would help clean the place out & brush the horses down for a few pennies. I never ever could stand the smell of the place. Another familiar face around the streets in those days were lamplighters. There were no electric streetlights around us, just gaslights. The closes were lit by gas. The lamplighters worked split shifts. They would start in the afternoon or early evening, depending on the time of year. They each carried a ladder & a little pole containing carbon, which they lit & used to ignite the lights in the streets & closes. They would then return in the morning & turn them off again. A favourite prank of schoolchildren in those days would be to get some carbon from the lamplighter & put them into the inkwells in the classrooms. This would cause the ink to bubble up & all over the desktops.

Immediately next to our building stood Stark's Paper Mill which had quite a large pond of water, which was always stagnant in the summer. The smell from it was appalling, wafting into the house if the windows were open. Our street Grovepark Street was known locally as 'doon the burn' so called possibly because Glasgow's famous Molendiner Burn ran underneath it on it's way from the north of the city down to the River Clyde. The Molendiner Burn was built over as Glasgow expanded. I've never been sure if it is the Molindiner that ran under the street. You can certainly hear water.

Ra burn also had a garage and a clothing factory. Also McPhaills Foundry that I can remember. It was also a good street to play. 'Tanner Ba' football, as there was no windows that could be broken. I started primary school in 1934 at the age of four and a half.

I went to Oakbank Street School , which was just up the road from us in Camperdown Street. Apparently on my first day, the teacher, a Miss Caldwell who was a wonderful old lady who had also taught my Aunt Sophie, called the register. On receiving no answer to 'Henry McIntyre` said to me "That's you." to which I apparently said "naw it's no. Ma name is Harry" Why do parents christen a child with one name and then call them by another?

During my years in Primary School, I was a bright child. I was always top of the class or thereabouts. In those days, the clever dicks sat at the top of the classroom and the dunderheids sat at the bottom. At the end of every month, the best pupil would get a Dux medal to pin onto their jersey for a month. I was a regular winner. There were about 40 children in my classroom. With my father being unemployed during the depression years of the thirties, my parents didn't have enough money to buy me school clothes, so my mother would have to apply to the Education Authority of Glasgow in Bath Street for me to get 'Parish Claes'. Parish Claes were instantly recognised as such. Boys would get a three piece suit in grey herring bone material. A jersey with red piping on it, two shirts and a navy blue tie with red stripes & pink woollen combinations which were most uncomfortable next to the skin. We also got a pair of 'tackity boots' with the letters E.A.G (Education Authority of Glasgow) perforated on to the ankles. This was to prevent parents pawning them!! Children, who's parents were unemployed, or on 'the buroo' also received free school milk, which normally cost a halfpence a day. Some children, who's father were fortunate to have a job could be very cruel to us unfortunates who had to endure the stigma of

"Free School Milk and Parish Claes.

Ach I suppose they were the good old days"

I can remember shortly after I started school, I was on a tram car with my mother and I started to read out an advert on the tram. I got a skelp on the lughole from her, saying 'You're no supposed to be at school yit!' She had been dodging my halfpenny fare. One of my earliest memories is being taken across the road to my Auntie Sophie's house because there was a fire in the house through the wall from us. I remember being laid at the bottom of her bed. When I mentioned this to my mother a good many years later, after some thought, she said that I couldn't possibly remember that incident as I was only about six months old. If she is correct about my age, it is a remarkable memory.

My home life in the early thirties wasn't a particularly happy period in my life. My father who was unemployed during the depression years, was rather fond of a drink and would sometimes spent more than he should have from his buroo money. He would also pawn something from the house to get money for drink and when he came back home there would be an almighty row between my mother and him. My mother would often physically assault him, giving him a black eye on occasions. To his credit he never laid a hand on her. I can remember on numerous occasions, as small as I was, trying to separate them. Ours was not the only around which had such ructions. Arguments could be heard from neighbouring households. Usually it was the husband who was doing the punching. What a helluva way to live!

Unemployment resulting in the loss of a mans dignity through not being able to support his family resulted in them turning to the drink for solace with no way out of the poverty trap. An unwelcome visitor in those days was the 'means test man' who would call on people who had claimed financial assistance and would assess the contents of their house, and would say "If you can afford carpets or a wireless, you don't need assistance from us." I can remember a neighbour bringing her carpets, wireless and some other things to hide in our house before the 'test means' man called on her incase he refused her claim.

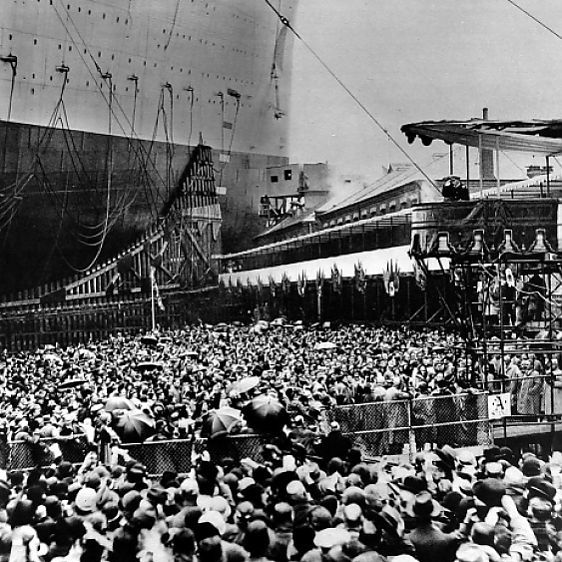

On 26 September 1934 I went with my father to Clydebank to see the launch of the Cunard Liner Queen Mary. I don't remember much about it. The only thing that stands out in my mind was being up to my ankles in mud. As a child, one would shout up to one's mammy "haw maw, gie's a piece" and she would throw one out of the window wrapped in newspaper. In my case it would be a slice of bread with margarine dipped in sugar. The better off children would get jam on theirs (a jeely piece.) One of my pals would get a piece and sauce.

There are a great number of contradictions of terms in Glaswegian dialect. For example, I would ask my mother for a penny for sweeties and back would come the reply "a penny for sweeties, I'll give you a penny for sweeties" That meant ye wurnae getting any. I remember a woman saying to her young son, "If you run out oanti that road and get killed, ah'll murder ye!!" Some games that we played as children were 'bools' (marbles). You could get multi coloured ones or large ones (plunkers). They were, if you were lucky enough to get them, large steel ball-bearings. Then the peerie season would come around. A peerie was a small wooden spinning top which would have chalk designs made on the top and you kept them spinning with a whip. Then there were the 'gird' season. A gird was normally a bicycle wheel with the spokes removed and they were propelled by means of a piece of wood. It's funny how the 'seasons' came around at the same time every year.

The seeds of religious bigotry are sown early in Glasgow when you start primary school and wondered why your pal went to a different school. Your mammy would say "he's no wan o' us." My primary school, Oakbank , was a non-denomination school, wrongly called a proddy school. It was immediately across the road from St Columba Catholic School. Stone fights would go on between the schools at 'play time'. We had to wait until the Catholic boys threw them first before we could return them. Their school was immediately next to an old quarry, where the ammunition came from. If people are integrated in collages and universities, why not primary schools? In Glasgow, there are too many Protestants and Catholics, but not enough Christians. In 1938, I like everyone else in Glasgow went to the Empire Exhibition in Bellahouston Park. It was a huge event. The day that I went was the day that I met the Old Dowage Queen Mother. She gave me a pat on the head. She probably couldn't resist such a handsome little lad like wee Henry.

The most traumatic event in my young life came in 1939 with the start of the Second World War. Just prior to the War being declared, all the children from the cities were evacuated to rural areas to escape possible bombings to the cities. I got evacuated to Dunblane with a family across the street from me, the McFarlane's, who were friends of my mother. I remember standing on Kelvinbridge Railway Station wearing a label with my name and address pinned to my jacket lapel. I had a tin mug on a string around my neck with a little cardboard case with my gas mask. I was 2 months short of my ninth birthday. On arrival at Dunblane, I remember all of us getting an Aero chocolate. Anytime I see this chocolate, it reminds me of Dunblane. We got billeted with two old ladies, of which, all I can remember is that they wore long black dresses. On my first night there, this being the first time I had ever left my parents, I 'peed the bed. I was mortified with embarrassment. So much so, I wanted to go back home to my mammy.

It was in Dunblane that I heard the then Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain declaring War on Germany on the 3rd September 1939. I was so unhappy there that my mother had to take me back home to Maryhill again. I preferred to go back home again and face any bombing than stay there. On returning home, I found that the close had been shored up with large wooden beams and a brick baffle wall erected on the edge of the pavement opposite the close. This was where the families were supposed to sit during the air-raids. When the first air raid siren sounded, we all trooped down to the close in our warmest clothing, with blankets and flasks of tea and pillows. The mammy's carried the birth certificates & insurances in their handbags. It was most uncomfortable sitting in the close. And cold too. After the first couple of warnings, everyone said 'sod this for a game of soldiers' and thereafter, stayed in bed. If a bomb hits us, the close won't save us.

Everyone in Britain got issued with a gas mask in case the Germans dropped poison gas bombs. They took a bit of getting used to. Everyone hated them, but I suppose they were necessary. We had to carry them at all times. I think that I once took mine out to the cludgie on one occasion. A good place to try them out I suppose! If the all clear sirens didn't go during the alert until after 2AM, the children didn't have to go to school that day. Needless to say, we all hoped that it wouldn't go until then. Everyone was also issued with an Identity card. The number on mine was 'SFFX 92 4. My fathers was 1, Mother was 2, my sister was 3 & I was 4.

1940s

The first 6 months of the War was known as the 'Phoney War' because nothing much happened on the home front. We had a barrage balloon sited up the road from us on an old quarry. The rather large balloons were filled with hydrogen and attached to trucks by a very long cable. They were to deter German dive bombers coming in low over the cities. If a gale blew up, they were brought down as soon as possible incase they broke away or overturned the truck. I don't know if they ever brought down any German planes, but they definitely brought down at least 3 British planes who's wings hit them. Our barrage balloon was manned by Polish airmen and it exploded and killed one of them. The Germans at that time in Europe were barbaric. They dropped poison gas bombs, slaughtered innocent people at sea, fishermen for example were continually machine gunned and their planes machine gunned refugees escaping from the carnage. One item of the news that came through at the start of 1940 was of a RAF operator who had to parachute out of his burning plane and who landed in full flying gear into a field of bulls. He apparently almost broke the 110 yard record to escape them. A piece of graffiti seen on a wall in Glasgow read 'England will fight to the last Scotsman' This was certainly true in June 1940 when the Scottish Regiments fought the rearguard action that helped 335,000 British and French troops to escape back to England in a flotilla of small boats from the beaches of Dunkirk in France. This was the most successful in Europe.

One of my uncles, Alex West, who was in Glasgow's regiment H.L.I. was reported 'missing in action' at the Battle of Dunkirk, and his wife, my Aunty Annie got word that he had been killed. She was allotted a War pension and she was about to draw it, she got word that Alex was alive and in a German Prisoner of War camp, where he spent the next 5 years.

The back room boffins in England, the university dons, professors etc, used to devise schemes to help prisoners of war to escape. One such scheme was to fit a small compass inside the brass buttons on soldiers caps. When the Germans discovered them, they changed the screw on them to a left handed one. Another ploy was for them to make small silk maps with escape routes from each of the camps. They were rolled up inside cigarettes with a little bit of tobacco at each end. A few years ago I asked my uncle Alex if he ever got any of them in his camp. He said 'Aye, the bastards, you'd be dying fur a smoke and when the Red Cross parcels arrived with the cigarettes, after a couple of drags, the fucking things would go up in a blue light'

A cousin of mine Tom Scott, got wounded in the face at Dunkirk, but he made it home on one of the 222 British naval and 665 other British crafts, plus the French vessels which took part in the evacuation. Another friend of mine Tommy McNamee, who was also captured by the Germans and he spent the duration of the war in a prisoner of war camp in Poland. He never tried to escape as he was safe there. Wise man. In fact he said they used to nip out to the local village at nights for a drink and then return to the camp.

Some odd facts came out during the war, for example:

*according to Dorothy Thompson, who was an American journalist, the Germans if they had succeeded in conquering Britain, intended to evacuate the British Isles, sending the Catholics to Ireland and the protestants to Canada.

*Every member of the Bakgatla tribe in the British Bechuanaland is contributing 5 shillings to a fund to help King George in his fight against the Germans.

*300,000 native mine boys on the Rand (South Africa) have clubbed together to contribute one shilling each a month to buy a battleship. I wondered if they managed it. I very much doubt it, but good try anyway.

*In 1942 Sten guns were being massed produced at a cost of less than £2. It was a good machine gun. I used one in training when I was in the RAF in 1949. Another uncle of mine Andrew Scott, who was my mothers youngest brother was in the Royal Navy during the war. He had joined the Navy as a boy entrant around 1919. He was a gunner on the huge battleship 'Duke of York'

which had a crew of around 4000. His ship was involved in The Battle of North Cape and the sinking of the huge German Batleship Schamhorst On one trip, it took the then Prime Minister Winston Churchill to America. Churchill gave all the ratings ten shillings each which was enough in those days to buy around 12 pints of beer. Andy on his return from America brought tins of malteezers for us children. This was unheard luxury for us as sweeties were rationed here. I think you got about 2 ounces a week. I had never tasted them before. I don't think they were on sale in Britain then. Whenever I see them in shops nowadays, I am always reminded of the wartime days.

If I can jump forward a bit, years later I was sitting next to my uncle Andy at a funeral service of his sister Annie. The minister was going on about what a wonderful person Annie was and Andy muttered to me 'Blethering bastard, a'h wish he would get on with it. He didn'ae even know Annie' A few years later when I visited Andy in Ruchill hospital, just before he died, he said to me 'A'm fucked Harry. The waterworks have gone' When I was at Andy's funeral in the same funeral parlour at Queens Cross, the minister was going on about how wonderful a person our beloved brother Andrew had been. I found myself muttering 'Blethering bastard, ye didn'ae even know Andy' When I realised what I had said, I started to laugh recalling Andy's words at my auntie's funeral. Everyone looked at me wondering what I found funny at a funeral. I would like to think that Andy was laughing too. Andy for some reason best known to himself, never married. I think he was too fond of his freedom and beer, not necessarily in that order. A friend of my mothers Cissie Wilson, who was about ages with Andy, had never married either and I think she fancied him. I used to kid him on about her. 'Dae ye no fancy gettit merrit tae Cissie Andy?' 'Aye that'll be fucking right, her bloody tongue never stops bloody wagging, she drives me roon the bloody bend, so she dis'. I liked Andy, with me losing my dad when I was a young teenager. Andy was like a second father to me. Many a good bevvy I had with him in the Royalty Bar in Maryhill Road, which was his local. He was always perched against the wall at the end of the bar. I still half expect to see him there yet. He probably still is in spirit if you pardon the pun.

After the retreat at Dunkirk, a Scottish soldier was heard to remark 'If England surrenders, it's gonny be a long bloody war' To paraphrase Winston Churchill's famous wartime speech 'We'll fight them on the beaches, hills, streets and doon the dunnies' The dunnies in Glasgow were at the back of some closes. You went down the stairs to the back yard. they were always unlit. Great places for taking your girlfriend or burd for a snogging session. This reminds me of the story during the Jacobite rebellion of 1745. A kilted Highlander stood on a hill waving his claymore, challenging the invading English army. The Duke of Cumberland sent up 5 of his men to get him. When they didn't return, he sent up another 50, and when they didn't return, he sent up another 100, one of whom returned cut to ribbons shouting 'Don't go up there, there's 2 of the bastards.'

Back to 3 June 1940, the Germans dropped 1000 bombs on Paris in a few minutes killing 245 people and injuring 652. The bombs had whistling devices on them to frighten the people. They lost 25 planes that day. The first major sea loss the Germans had was the sinking of the mighty battleship Graf Spee in Buenos Aires. The captain committed suicide a few days later. The nearest a bomb fell to us in Maryhill was a landmine which landed near the bridge in Queen Margaret Drive. The blast blew my sister Annie out of her bed, She had been sleeping in our Aunty Annie's house in Vernon St which was about a half mile or so from the blast. Another bomb landed in Kilmun St in Maryhill, killing I believe 83 people. Another bomb landed not too far as the crow flies on a bridge in Kelvin Way at the back of the Glasgow Art Gallery in Kelvingrove Park. There is a commemorative plaque there telling about it.

After the air raids we children used to search the streets for shrapnel. We used to think that they were part of German bombs, but they were more likely to have been parts of anti aircraft shells from the gun sights around the city. The sky would be criss crossed with searchlight beams looking for German planes. I wonder what ever happened to my collection of shrapnel?

I can remember being with my mother in Possilpark in the North of the City, visiting her friend Mrs MacFarlane or 'Faurlie' as she was known, when Clydebank got blitzed. With Possilpark being one of the highest part of the city, we could see the sky over Clydebank lit up by the flames as we made our way home. I don't think we should have been out in the streets during the raid, but my mother must have wanted to get home. The next day, I went with my mother to Clydebank to see if her cousin Kate Scott, who lived there was alive. I well remember the railway bridge at the bottom of Kilbowie Road shored up with huge beams and the nearby buildings lying in rubble. I can remember seeing a child's doll lying there. It was a sad sight. My aunt Kate lived up near the top of Kilbowie Rd in Second Avenue. There was only one wall of her building left standing. After visiting some hall or other my mother found that Kate and her family were alive. Fortunately they had been in the cinema at the end of their street during the blitz, which escaped the blitz.

I believe about 500 odd people got killed that night. The German bombers followed the River Clyde to Clydebank. How they missed the huge Singer factory or John Brown's shipyard I'll never know. They only suffered minor damage. The shipyard and the factory were the probable targets for the bombers. On another night, we could see from Glasgow the sky lit up when the oil tanks at Bowling got hit. Apparently the first bomb to land in Britain landed in the Orkney's killing a rabbit. This inspired the very popular war time song 'Run rabbit run'. The German plane probably jettisoned his bomb before returning to Germany claiming that they had hit their target. I believe some British bombers did the same. Dallied about over some relatively safe air space, dropped their bombs anywhere rather than face the German bombers and anti aircraft guns. They would never admit to it though. Who can blame them. War kills people. Around 1941 or so, the Germans aircraft factories stopped building bombers and started building fighter planes. They realised that the writing was on the wall and they prepared to defend the Fatherland. When the United States entered the war in 1941, on top of the Germans declaring war on Russia, it was only a matter of time before they were defeated.

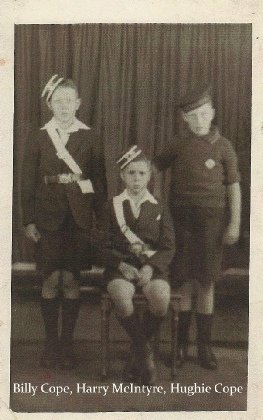

About 1942, I left my primary school after passing my 'Quali' exam as it was called. I can remember getting 100% for arithmetic. I would like to have went to Allan Glen school to further my education, but it was a fee paying school which my parents couldn't afford. I went to North Kelvinside Secondary School in Oban Drive in Maryhill and stayed there until 1944 where I left with no qualifications. To be honest, I don't think that I tried too hard at science, algebra etc. Around 1942 I joined the Boys Brigade movement after being a 'life boy', the junior movement of the Boys Brigade. This was, and probably still is a paramilitary organisation run by the Church of Scotland. The movement started in North Woodside Road in Maryhill. We learned formation marching, arms drills and how to use semaphore signalling with flags. I suppose we were being trained to be cannon fodder for any future wars. We also had to attend bible classes. This possibly was also to learn us to pray if we got shot in any future wars I suppose. I'm being rather cynical, but that's the way I felt. I was a member of the the 232nd Company of Glasgow which was attached to a Church in Raeberry Street in Maryhill. My 2 cousins Billy and Hughie Cope were also members of the Company.

I suppose the highlight in the Company was when the Glasgow battalions got an invite to parade around Hampden Park an the interval of a Scotland v England football international. Scotland got gubbed 6 something or other.

In 1942 I got my first job, when I was 12 years old. I started at 4:30pm after school until 6pm delivering customers orders for a fruit and veg shop in Woodland Rd. I earned the grand sum of 2 shillings and sixpence a week (12.5p) plus any tips from the customers. The children had to get permission from the authorities to work after school. I think that I got to keep a shilling and my mother got the other shilling and sixpence. I left school at the end of 1944 aged 14. I then got a job as a message boy for a chemists shop in Great Western Road. I had a bicycle with a pannier in front and back of the bicycle for sitting baskets or boxes in. I got paid the grand sum of one pound a week. Such wealth. In 1944, when I left school I was allowed to wear long trousers. I was very self conscious about wearing them. I thought everyone would be laughing at me. The smallest children nowadays wear them. How times change.

I left my job in the chemists and went to work as a message boy again in Chalmers Stores which was an ironmongers shop at 683 Great Western Road (Now a hair dressers shop.) Again I earned a pound a week plus tips. Needless to say, the customers that were good for a tip got their orders first, especially if I was skint. Instead of a bicycle, I had to pull or push a rather long barrow. It had long shafts, connected at the end with a spar, and I had to get inside the shafts and pull it like a bloody horse. All for a pound a week, later to go up to 30 shillings. Its a wonder they didn't give me a tail light to hang onto my arse for when it was dark. I suppose it must have been dangerous being on the roads without a light. I used to deliver boxes of firewood (or sticks), cans of paraffin, preserving jars, handwringers etc to name but a few, around the Hillhead and Kelvinside areas. During the War, there was a blackout. Every window had to be covered with heavy curtains or black blinds so that no light showed what so ever. The windows also had sticky tape on them incase of bomb blasts. There were no street lights. Cars and bus headlights had blue diffusers on them. If you carried a torch, it had to be covered with a blue handkerchief or paper. People were forever walking into lamposts and 'baffle walls'. There were air raid wardens who went around the streets looking for chinks of lights from windows. If they saw any, they would blow a whistle and shout 'Put out that light'. I don't think people were even to walk about with a lighted cigarette in their hand incase a German bomber saw it. Highly improbable I would think. On my fourteenth birthday in 1944, the mighty German battleship ' Tirpitz' got sunk by RAF bombers.

When the Germans surrendered in May 1945 V.E day, there were great celebrations in Glasgow. Streets were bedecked in bunting and flags and street parties were the order of the day, We built a bonfire in our street. We took down all the wooden beams that had shored up the closes, praying that the buildings wouldn't fall down. The heat from the bonfire was so great many windows cracked. To this day, nearly 50 years later, the mark of the bonfire can still be seen on the cobble stones off Grovepark St & Hopehill Rd in Maryhill. I can remember on that night as we round different bonfires, I got grabbed by a girl and given an almighty kiss. My first kiss by a girl and I liked it. The war against Japan finished soon after the Americans dropped 2 atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Is was a pity they never dropped them on Tokyo and Asaki, their major cities. The Japanese had been more barbaric than the Germans.

There were a lot of welcome home parties for the returning troops. wearing their de-mob suits, instantly recognisable (Shades of Parish claes?) In 1948 I left my job as an errand boy with the ironmongers, something I should have done when I was 16. It's a pity my parents never made me start as an apprentice or something. At 17, I was too old to start one. How it came about, I don't remember, but I joined the LNER Railway as an engine cleaner. This was my first step to becoming a fireman and then a train driver. I was employed at Stobcross Locomotives Power Depot on Kelvinhaugh St Finneston at a wage of 5 pounds 3 shillings a week. A great jump from the £1.50 I was getting at the ironmongers. I started by cleaning the steam locomotives with paraffin rags, polishing brasses and filling sandboxes, which had a pipe running down from them to the rails. These were used if the engine wheels started to slip on wet or greasy rails. I progressed from cleaning to fireman on the locomotives. We only worked on goods trains and shunting jobs in the docks from Stobcross. I rather liked working on the footplate as I wasn't stuck in the same place every day. You never knew where you were going until you reported for work. I got into the habit of looking into house windows as we ran alongside houses. I still do as I pass houses. I'm still a nosey bugger. The only thing I didn't like about the job was working shifts. You had to start and finish at all hours of they clock. Working on a Saturday afternoon or night was a bugger. Your pals would be going out to enjoy themselves and you were going to work.

On the 29th December 1948, my father, who had been ill with cancer of the stomach for about 18 months, died. I was in bed when my mother came 'ben the room' and said 'he's as deid as a doornail' He got buried on the 31st December (Hogmanay.) That night I took my mother down to her sister Sophie's house before 'the bells'. I could hear people in the neighbouring houses celebrating the New Year and I remember saying 'They bastards are singing and ma dad's deid' but of course he wasn't their loss. Young as I was that night, at 18 I drank more than a bottle of whisky and was still on my feet at 06:30 as was my brother Duncan. Everyone else was out for the count apart from the women who didn't drink. I remember being most upset at my fathers only brother Jock, who said he couldn't come to the funeral because he had a milk run to do. I told him to fuck off and never come near us again. He never did to the best of my knowledge.

April 1949 was the beginning of a new phase in my life. I was conscripted into the Royal Air Force to do my 18 month compulsory service, much against my wishes I may add, but I had no choice. I didn't want to leave my recently widowed mother on her own. I reported to Padgate Training Camp near Warrington to get kitted out and do some preliminary training for a week. I was made to have two haircuts in my week there. 'Am I'm standing on your hair airman? I should be, I'm standing on your bleeding hair. Get your hair cut' 'But I've just had it cut!' 'Get it bloody cut again' After a week at Padgate, I went to West Kirby Camp near New Brighton to finish my eight weeks training. The drill movements I found easy. I had done them in the Boys Brigade. My serial number was 2429509. It's amazing how one never forgets it. I have asked numerous people what their serial number was and they never forget even after a space of 50 years. For some, it still trips off their tongue.

On the drill ground on one occasion, I made a mistake and the instructor said 'You're a silly airman, what are you?' I replied 'I'm a Scotsman Corporal' As he was as well, he only laughed. On my first visit to the rifle range, when my target was brought back in the instructor said 'You'd be better putting a fucking bayonet on it and charging Mac' On passing out from West Kirby as a A/C2 Plonk. I was posted to Compton Basset Camp in Wiltshire where they proceeded to train me as a telephone switchboard operator. A big change from shovelling coal into a railway locomotive. After a couple of months I was posted to RAF Feltwell which was a flying training school. Real planes and everything. This was more like being in the Air Force. I was the only lad in the telephone exchange and I got spoiled rotten by the girls. They kept me well supplied with tea and buns. My Glaswegian accent caused a bit of bother. Most people on the phone couldn't understand me. They made a recording of my voice and played it back to me and I was amazed at how broad I sounded. I then had to modulate my accent so that the English could understand me. Its funny how the Scots can understand the English, but they can't understand us.

At Feltwell I managed to get my place on the station football team at left back. This was a great skive. You got time off for training and you visited other stations to play against them. In Norfolk at this time one could buy a pint of 'scrumpy' for nine pence (4.5p). On a particular night out, one of the lads drank 9 pints of the stuff in an hour. I carried him back to the camp on my shoulders. A pub there also sold a drink that cost 2 shillings and sixpence (12.5p) a pint. It was about twice as quick as Guinness and they would only sell each customer two pints as it was too potent. When my training as a telephone operator was complete I got posted to RAF Breighton near Selby in Yorkshire, For some reason or other I had to spend a long weekend on route to RAF Heywood near Manchester. I took the opportunity to watch my first English football match at Maine Road Manchester. When I arrived at RAF Breighton, I was shocked at the place. It had been a wartime airfield, but now it was only a store. The hangars were full of surplus furniture etc rounded up from all the wartime airfields. Lorries would come in and take the stuff away to be auctioned. There were only 19 personnel on the camp and a scruffy lot I had never seen. Before long, I was as scruffy as the rest.

My job was to operate the switchboard, if it could be called that. It only had two outside lines and ten internal lines. The switchboard was situated in what was once the guardroom. There was a barrier outside it across the road which I opened and closed. To allow the farmers who leased the land between the runways access, I also had to book them in and out of the camp in a book. The commanding officer was a Flight Lieutenant called Nops. He was some turnout. He would roll up to the camp in the morning wearing his cap and great overcoat over a sports jacket and flannels. Sometimes only his pyjamas. On one occasion we were to have a visit from a Group Captain and Nops gathered the 19 of us together saying "You bastards never salute me. You had better do it when the Group Captain comes" The first time I passed him after the Group Captain had left, I saluted him to which he replied "Fuck off, Mac." On the subject of saluting, on a visit home to Glasgow, for some reason or other, I was wearing my RAF uniform walking along Sauchiehall St when I passed a RAF officer. Without giving him a second glance he shouted to me "Airman, don't you know you're meant to salute an officer?" His face was a picture when I told him to "Fuck off pal, you're in Glasgow now" and gave him the two finger salute. Back at Breighton we braided the hangars for furniture for our billets. We had curtains on all the windows, two mattresses on each bed, an easy chair and a wardrobe each and the floor was covered in carpets. We must have had the most comfortable billets in the whole RAF.

One of the lads had a wonderful collection of Victorian postcards. They had words and music of some old time songs. He and I used to go into a converted gas shelter, where there was a grand piano, wherever they stole that from. Dinsley played the piano and I sang the songs. The acoustics were great in there. It made me sound almost good. We also held whist drives in there inviting the locals in. The profits we made went towards buying a set of goalposts and a set of football strips. We managed to wrestle up a team from the 19 of us. On one occasion we played a team from RAF Church Fenton. One of their players was a right dirty bugger, so I decided to sort him out. I deliberately back headed him when we went for a ball and I broke his nose, proclaiming that it was an accident of course. As we were only a small camp, we had to collect our rations from Church Fenton and a few days later I was on the lorry to collect them and who was on the main gate? A sergeant in the RAF police with a plaster across his nose. I made sure he never saw me on the lorry. To supplement our meagre rations, the local farmers used to lend us their shotguns to shoot rabbits, who were a pest to their crops. We were forever spitting bits of buckshots out of every mouthful.

There were a lot of huts about the airfield with their doors swinging open, so the C.O gave me a large bunch of keys and asked me if I could find one for each of them There was an unusual key amongst them. It was a skeleton key. It opened every mortice lock in the camp. I kept it for myself and used it to open our larder after our nights out. We would have a fry up in the billet. Most of the huts in the camp had posters on their walls. German aircraft identification, warning posters about 'careless talk' which could cause lives etc. They would be a collectors item nowadays. I said to the C.O "There's only one gun on this camp and its your bloody revolver. What would we do if someone attacked us? I'll see what I can do" he said. True to his word, he managed to obtain a rifle, a sten gun and a bren gun with lots of ammunition. I used to go up to the old rifle range with him and have a go with all the guns. I became quite a good shot. I certainly had plenty of practise. I don't remember if the other lads got a chance. They probably did. If there was a skive going, they would have been part of it. The C.O used to give us the use of his lorry every Saturday morning to go into the local town of Selby to get a haircut. He said one day" How is it that none of you bastards ever come back with a haircut?" The reason was that we used to go into the town and meet our girlfriends. I volunteered to babysit for the C.O one night. The rest of the boys said "Fucking crawler" but when I came back half cut with a half bottle which contained a mixture of whisky, gin, vodka, which Nops had told me to help myself with from his cocktail cabinet, they all wanted to be crawlers and babysit.

1950s

About 9 months into the 1950s, the CO came into my office and said 'I've got good news for you Mac. I've got you a posting to Edinburgh' to which I replied 'Who the Hell wants to go to Edinburgh? I'm quite happy here' 'Oh' he replied 'I thought you would want to be nearer home' but it was too late to cancel it. My best friend at the camp Bill Paterson, who came from Dalmellington in Ayrshire, couldn't bring himself to say cheerio to me before I left. Bill and I had one of those close relationships that seem to happen in the services. We went to wash, ate our meals and went on the 'randan' together. When he was stuck for something to put in his letters for his girlfriend, I would write him out some sentimental rubbish to put in his letter. He would do the same for me when I was stuck for something to write to my girlfriend. I think my sentimental mush did more for his relationship than his did for mine. He got engaged and wee Cathie gave me the elbow.

My new posting was to Kirknewton near Mid Calder, not too far from Edinburgh or 'Embra' as we Glaswegians call it. This camp was a huge bomb dump. All the surplus bombs and incendiaries were collected from all over Britain and taken to Kirknewton. We used to build the incendiary bombs in a semi circular wall, about 3 feet high. First removing the explosive ones which were painted red, to prevent the rest being scattered all over the place. The incendiaries contained magnesium and when we set them off, they went up in a lovely blue light. There was a no smoking ban near the other bombs, but of course, no-one paid a blind bit of notice. We would sit on 1000lb bombs and have a puff. The bombs, other than the incendiaries were loaded onto lorries and taken down to Ardrossan, loaded onto a ship and dumped in the Clyde estuary. God knows how many thousands of tons are down there.

I had to work a shift operation on the switchboard which was much bigger than the previous one that I worked. I worked a day and a half then I would be off for two and a half days. I was home more than I was in the Air force. As I was working in the railways before I got called up, I had cheap rail tickets. I could get a return ticket for half the price of a single, which came in handy when travelling to and from Glasgow. At Kirknewton I made the station football team which surprised me because they had some good players there, Scottish of course. We played other RAF teams and such as Edinburgh University. It was most enjoyable and a good skive from ones duties. A posting came up for a RTO. I understood that RTO stood for Railway Transport Office, which most large stations had at that time, to assist any serviceman who had travelling problems. These were always 'home postings' and I thought that I would spend the last few weeks of my RAF service in Glasgow Queen St or Central. The conscription period of 18 months got extended to 2 years, so I would be in for another 6 months. I was successful in getting the posting, but to my chagrin, RTO stood for Radio Telephone Operator and I was posted to Gloustershire. When I arrived RAF Aston Down near Stroud, I discovered that this was a proper aerodrome, pilots, planes and smartly dressed personnel. I remember thinking to myself 'Christ whit have I lit maself intae?'

I was assigned to air traffic control and worked in the control tower which was manned by a mixture of RAF personnel and Ministry of Defence civilians. My job was to pass landing instructions to the aircraft over the radio telephone, giving them the runway in use, wind speed, cloud base levels etc. My Glaswegian accent was thought to be a problem. We transmitted on a very busy frequency, used by all the surrounding airfields and it was difficult for the pilots to know which airfield was calling who. As I was the only operator with a Scottish accent, they knew that it was Aston Down calling and my accent was now an asset. Another part of my job was to man the 'homer'. This was set up in a caravan in the middle of a field. This was used to guide planes back to Aston Down if they lost their way. It had a 360 degree wheel and when the pilots transmitted for a bearing, the wheel was slowly turned until their voices faded away through the headphones we wore and there was a dead space. This gave us a reading on the degree wheel an this was the course that they could turn on to, to get to Aston Down. By this means, we could bring them right down over the runway. The system is much more sophisticated nowadays. In the 'homer', one had to be careful. The degree wheel had 2 dead spaces on it. One gave a reciprocal reading which would send the planes away from the airfield. This could have had disastrous consequences for the meteor jet fighters of this time. They could only carry enough fuel for one hours flight and we had to inform them when they had been airborne for half an hour and then every five minutes thereafter. Luckily I never gave any of them a reciprocal reading.

At this time I received £4 10 shillings a week, which wasn't too bad for being in the services. It was only pocket money as I didn't have any food or board to pay for. The civilian that I worked with, Harry Firman, had even less than that to keep his wife and baby son in a rented room. Just before Christmas 1951 I won a raffle in a draw. The prize being a turkey. As I wasn't going home until after the New Year I gave Harry the ticket to collect the turkey and have it for his family. He wanted to pay me for it, but I wouldn't hear of it. The next day he came in and said that he had to pay me for it as it weighed 22lbs, but I still wouldn't take any money from him. He then invited me to have Christmas dinner with him and his wife in Cirencester where he lived. His wife couldn't get the turkey into the little oven that they had, so she had to take it to the local baker who cooked it in his kiln. Harry was sick of eating turkey long before it was finished and he would bring some in for me to use it up.

Around this time I saw the maiden flight of the Giant Brabazon plane from Filton Aerodrome near Bristol. It was a huge monster. It could hold 6 double decker busses end to end. I never heard much about it after that. I suppose it was too big at that time to be practible. I did a very foolish thing at Aston Downs. Through my inexperience around planes, I was sent down to the runway concourse to open the hatch under the cockpit of the mosquito fighter bomber, to let the crew out. I don't know why they couldn't open it themselves. Anyway, after I opened it, instead of going back towards the tailend, I walked out between the twin propellers which were still rotating. They were going so fast they were almost invisible. I must have been within an inch or two of being cut to ribbons. The people in the control tower who were watching me were horrified. I was very lucky. I guess my time hadn't come.

One of the air traffic controllers, a Flight Lieutenant Doig, who liked to be called Captain as he was a South African. He invited me to go up in a plane for my first flight. The others in the control tower advised me not to go up with him as he was a bit of a madskull. I remembered that as I walked out to the plane wearing a parachute. I was shittin' myself. Once I got strapped in to the plane, I was alright and I rather enjoyed myself. Captain Doig didn't fool about (this time). On my second flight with him, he said he was going to make me sick. He started flying upside down and doing loop the loops and went down into a steep dive to show me where one of his 'popsies' lived over Swindon. He pulled up only a few hundred feet from the ground I think, for I had my eyes shut. I wasn't sick, but I was mighty glad when we landed. I went up several times more with him and he used to let me pilot the planes for spells. We used a 'Tempest plane' which was American built I think. There were a few Polish pilots at Aston Down who had fought in the Battle of Britain in 1940, they were a devil may care lot. One of them told me they used to machine gun any German air crewmen who parachuted out of their burning planes. This wasn't considered 'cricket' by the British pilots, but the Poles said that it happened to their pilots by the Germans and it was also revenge for the German destruction of Warsaw.

On a visit to a pub in Stroud in the company of one of the lads, there was a sing song going on. I got up and sang an Irish song 'I'll take you home again Kathleen.' The next thing 2 pints got put down in front of us. The place was full of Irishmen who were doing a contract job in Stroud. We never had to buy a drink all night or any other night that we were in there. My friend Derek said 'I'm coming out with you every night Mac, this is great' I spent weekend with Derek at his home in Hanley which is one of the five towns in Stoke on Trent and visited the pottery where his mother worked. She painted flowers etc on the china before it got fired. From there I bought a white china half tea set for six shillings and sixpence (35p)

When my demobilisation date came around this time, I seriously considered re-enlisting as a regular in the RAF. I rather liked the life now, but with my mother being a widow and living on her own, I felt that it was my duty to return home and support her. I resumed work as a railway fireman on my demob, but in my absence the railway companies had been nationalised and were now called British Rail.

The motive power depot at Stobcross, where I had previously been employed had been closed and I had been transferred to Dawsholm motive power depot in Maryhill, which was nearer home for me. My mother had now moved house to 24 Fernie Street Maryhill. The old building at Grovepark Street being demolished. This was a better house. It even had electricity. Still only a room and kitchen though. I think that on resuming my railway service was £7.14 shillings. Dawsholm worked a mixture of passenger and freight trains. We were known in the railway circles as 'The Dawsholm Rats' because most of our trains ran underground no matter what directions our engines left the depot, which was situated behind Maryhill Barracks. We had to go through tunnels in one direction to Possilpark, running under Ruchill Golf Club. In another, under the Botanic Gardens. In another to Partick, we ran all the way to Dalmarnock and Parkhead, running under Argyll Street, listening to the tram cars rumbling overhead. We also worked through the Queen Street tunnel to High Street.

In those days of steam trains, the tunnels were usually thick with smoke. You couldn't see much in front of you, but we always knew where we were. We knew the contours of the 'road', the inclines and the bends. We could almost go through them blindfolded. God knows what the smoke did for our lungs. We would be spitting black phlegm for ages. If you lit a cigarette, it nearly killed you. One amusing incident happened around this time. On completing a local passenger run from Rutherglen, we uncoupled the engine in the yard at Maryhill station (Now a Co-op supermarket) and drew up to the signal to let us cross the main line to out depot. This was at 6pm on a Friday night, the driver, the guard and myself wanted to finish as soon as possible as we all had somewhere to go. We were still sitting at the signal at 6:30pm. The guard got exasperated and said to wee Rab Williamson, the driver, 'Ah'm gaun up tae that signal box tae chew the baws aff that wee cunt' Wee Rab, who had a stutter said 'Ye be better no no dae that Wullie. You're a catholic. Ye ye ca ca canny eat meat on a Friday' I nearly fell off the engine laughing. I tittered all night after that thinking about it. Another tale about wee Rab comes to mind. My pal John Milne and I were playing a 'bools' tie against wee Rab and another old engine driver Jock Barrie. Rab flung up his bool on one occasion and shouted to Jock 'How far away is ma 'bool? fae the jack?' Back came the replt 'aboot the length of your cock Rab!!' 'Oh as faur away as 'a that?' On one occasion his brother in law came to his door one night and said 'Ma wife's left me Rab' Rab replied 'some cunts have all the luck' He got no sympathy from Rab.

I progressed from being a fireman to what was called a 'passed fireman'. I had passed my practical and oral examinations, which allowed me to drive trains. One had to know every part of the locomotive from one end to another. What each part was called, where it was situated, what function it played and what to do if it malfunctioned. One really had to have a comprehensive knowledge of a locomotive. One also had to know all the rules relating to safety regarding running trains. Before one could drive a train anywhere, one had to know 'the road'. This meant for example, to drive a train from Partick to Perth, one had to know where every signal was situated, what it told you, where every station was, every gradient, curve in the road and any speed restrictions that may be in force. After learning all this, you signed a 'route card' saying you were fully conversant with all aspects of this route, then you built up other routes. It was against the rules to run a route that you hadn't signed for. If you had to run over a route that you hadn't signed for, you could ask for a conductor to take over the train. He, of course, would be conversant with the route.

We used to run football specials to run from Possil to Parkhead and Ibrox on match days. I remember driving a special from Parkhead one day, which had seven old style coaches and I estimated that when I left Parkhead station, I was carrying over 1000 passengers. It was a sobering thought to realise that you had all their lives in your hands. One Saturday, we were short of an engine to work a Rangers supporters special. We had to borrow one from Kipps depot. They sent an engine called 'Father Primrose'. Someone must have had a twisted sense of humour. The engine got abused by the Rangers fans 'Who the fuck put that engine on oor train?' bombarding it with wine bottles. I am glad I wasn't on the footplate that day. The majority of our trains carried iron ore from Rothesay Docks at Scotstoun to the ironworks of Lanarkshire, Clyde ironworks, Gartsherrie, Dalziel and Ravenscraig. We stockpiled Ravenscraig with one million tons of iron ore prior to its opening. The steel works have all nearly gone now. We would carry about 330 tons of ore at a time on the trains. Quite a heavy load to pull up the hills and quite difficult to stop going downhill.

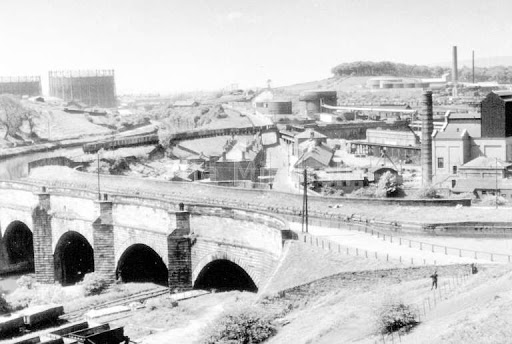

There was an interesting feature down at the end of Dawsholm engine sheds. There was a railway viaduct running between water. The River Kelvin ran down below. The viaduct over it carried a railway line into Anniesland Gasworks and over it a viaduct carrying the Clyde and Forth Canal. It was conceivable that a train could have run between the boats. One of the wonders of Maryhill. Around this time in 1951/2, a knock came to our door one day. It was a postman with a kitbag belonging to my brother, which he had lost in the Western Desert early in the war, about 10 years earlier!! God knows where it had got to. It didn't contain very much. Some books, a pewter tankard and a pair of football boots with v-shaped bars on them for playing in the sand. I commandeered them.

I was playing football for our railway team on a Tuesday afternoon shopkeepers league, that being the traditional Glasgow half holiday at that time. It was easy to book a park on. We played most of our games on 'junior' park. Our home games were played at Kelvindale Park which was the home of Maryhill Harp. I think we hired the park for £1 a game. Other teams in the league were from the larger stores in Glasgow, the Post Office and the other Railway teams. Playing on a Tuesday left you free to watch the senior teams on a Saturday, that is, if you weren't playing for another team, which I was. I also played for our local street team called Hopehill Star. Through raffle tickets etc, we used to make around £20 a week which was quite a lot in those days. We could afford to buy our strips from a company that made them for English first division teams. We wore maroon and white vertical stripes. We were well supported on away games. I've seen us with three double decker busses of supporters following us. Some support for a street team.

My football allegiances was always split between Partick Thistle who's park was only 5 minutes walk from my house and Rangers . I never liked to travel too far outside of Glasgow on a Saturday, because I liked to go dancing at St Andrew's Hall. It was so popular that you had to queue up to get in, no later than 6pm, so I would go and watch whatever of the 2 teams were in Glasgow. Sometimes I even went to see Celtic with my pal Bill Hearns. I was never too biased. I didn't care who beat Celtic. I was part of several crowds of 134,000 who watched Rangers in those days. The all seated stadiums of today can't hold anything like that. I've been in Ibrox crowd of 90,000 plus and 80,000 in Celtic Park. Most Sundays we would play scratch games of football amongst ourselves on an old quarry at the top of the 'burn'. These games would go on all day. You left to go for your dinner and then your tea, with someone taking your place. You then went for dinner and then your tea. These games would finish 64-62 or something like that. Everyone had to take a turn in goal, which nobody ever wanted to do. Some Sundays I would met my pals when they came out of 12 o'clock mass. I was the only 'proddie' in our crowd. We would go to our favourite cafe, 'The Bar Italie' in Maryhill Rd and have ice cream in the summer and hot drinks or hot peas and vinegar in the winter. The Italian cafes were about the only places open on a Sunday in those days much against the wishes of the Church of Scotland.

We would then go for a walk if it was dry 'up Sauchie, doon Buckie' (up Sauchiehall Street and down Buchanan Street) and make our way to 'Ra Barras' at London Rd listening to the patter of the street traders. Some of them were funnier than professional comedians. One of them one day was trying to sell razor blades '50 furra shilling'. He asked the crowd 'Hiv any of you ever used them?' Getting no reply he said 'Have any of you ever tried to use them?' On wet Sundays, we would quite often go to the Glasgow Art Galleries. This was always good for a laugh. Someone would always come up with a corny remark about some of the exhibits. I was usually the culprit. On wet Sunday nights we would quite often sit on the first flight of stairs up a tenement close in Hopehill Road, maybe about a dozen boys and girls singing and harmonising the latest popular songs of the day and yesterdays. This was before anyone had television sets. I don't remember any of the people who lived up the stairs complaining. They must have liked the singing!! Some of the songs that were popular in Glasgow were,

Aura : Pale moon shining

Ammonia : A strolling vagabond

O'Hara : Deep in O'Hara Texas

Sunday nights were also our card school nights. We played in John Connichie's house. John had a radiogram and we would listen to records by such as Nat King Cole, Perry Como, Bing Crosby and Guy Mitchell. We would chip in and buy the latest records between us for John. We would play 'Newmarket' and the stakes would only be for a halfpenny. I was very keen on dancing, or as we called it 'ra jiggin' I learnt it an an early age, about 14 or 15 in the local catholic parochial hall in Cameron Street. I was the only 'blue nose' who went in there. I got a lot of good natured banter. Being so young, whenever a 'ladies choice' was announced, all my pals and I was rush to the cludgie incase a girl we didn't like asked us to dance. I gradually progressed to being a 'rerr dancer'. I was particularly keen during a quickstep to 'birl' in the corners which resulted in the MC shouting 'Nae birling in the corners' I was pretty light on my feet in those days and could gallop about the floor. I also started to go to the Highlanders Institute which had Scottish Country Dancing or to use a derogatory term 'Teuchter dancin' This was very energetic, but great fun. We used totake our sandshoes to dance in. We soon picked up all the dances, Dashing White Sergeant, Highland Scottiche, Lotties Jig and so on. My favourite hall was the St Andrew's Hall, now the Mitchell Theatre and library. It had two halls. One large with a big band and a smaller hall that had a four piece Jazz Band. This was my favourite. Plenty of opportunities to 'birl in the coarners' to the fast numbers. I also went dancing to the Albert Ballroom, The Berkekey, The Locarno and The Plaza. The Plaza was rather posh in those days. It was couples only except for a Tuesday night. Before my time gentlemen had to wear gloves or hold a handkerchief in their hands to prevent soiling the ladies dresses.

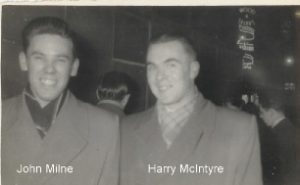

Around 1955, I went on my first continental holiday with my friend John Milne  who worked with me in the railway. We went to Ostende in Belgium using our free passes from Glasgow. Used privilege tickets on the cross channel steamer which allowed us the return fare for half the single fare. The brochure that we booked the hotel from stated that it was only 10 paces from the beach, English spoken and music with your meal. It sounded great. You would have needed to be a giant to reach the beach in 10 paces. As for the English spoken, the old guy at the desk could only say 'Good morning, good afternoon' and he couldn't tell the difference between them. The music played during meal times came from an old pre-war radio. A lady showed us to our room. We went up three flights of stairs, then a bloody ladder, through someone's attic room then to a box room. We refused it telling her to stick it up her 'gonga' to use a good Glaswegian phrase. She got the message and gave us a room each in another hotel they had across the road. Talk about disillusion.

who worked with me in the railway. We went to Ostende in Belgium using our free passes from Glasgow. Used privilege tickets on the cross channel steamer which allowed us the return fare for half the single fare. The brochure that we booked the hotel from stated that it was only 10 paces from the beach, English spoken and music with your meal. It sounded great. You would have needed to be a giant to reach the beach in 10 paces. As for the English spoken, the old guy at the desk could only say 'Good morning, good afternoon' and he couldn't tell the difference between them. The music played during meal times came from an old pre-war radio. A lady showed us to our room. We went up three flights of stairs, then a bloody ladder, through someone's attic room then to a box room. We refused it telling her to stick it up her 'gonga' to use a good Glaswegian phrase. She got the message and gave us a room each in another hotel they had across the road. Talk about disillusion.

Ostende was rather a nice little place with plenty to do for the holiday makers. We paid a day visit to Bruge which was a delightful little town. It had a network of canals. A sort of miniature Amsterdam. It was the most noisiest little town that I have ever visited. It had a large number of churches and training colleges for priests and nuns. All the church bells rung continually. Loudspeakers were strung across the street playing music from the local radio station. Brass band marched up and down the street all day, da da da da!! I wouldn't have liked to have lived there having a nightshift job. You wouldn't have got much sleep. That day in Bruges, we experienced the heaviest downpour of rain that I have ever seen. We ran for cover into an old pub. There was an enormous old man weighing over 20 stones with hands like a bunch of bananas, playing a bunch of bells. There must have been about four dozen bells of assorted sizes and he could play anything on them, replacing each bell back in it's own place in the box. A campanologist extraordinaire!! After an enjoyable week in Ostende, we went to Brussels for an overnight stay, but we weren't too impressed with the place. A doorman outside a sleazy place tried to entice us in, upon us saying 'no comprende' he tried 'Parlez vous Francaise' 'Sprachen de Deutch, American, English???' When he finally gave up, I told him we were Scottish. He said 'Ah Jocks!!!' I said, 'no, he's Jock, I'm Harry' We went into the club for a nosey and bought a drink. Two hostesses came over, but they didn't get a drink or anything else from us. We 'shot ra craw' pretty damn quick.

The Belgian toilets in those days were something else. They were common between men and women. It was very embarrassing standing at a urinal with women passing by. The posers who were 'hell hung' would stand proudly and let it all hang out and the titch's would try to hide their embarrassment. I'm not saying which category I came under. My pal John got caught short on one occasion. I followed him into the toilet a couple of minutes later and he was leaning against a wall, trousers around his ankles, feet straddled over an open hole in the ground doing a 'jobbie' I was sorry that I never had a camera with me. We left Brussels and spent an overnight stay in Luxembourg. There wasn't too much of interest there. We returned to Ostende, stayed the night then returned home. It had been an interesting experience. The next year John and I went to Spain on holiday using our free rail passes and concession tickets. It cost us £5 in total to travel there and back and that included a sleeper on the train from Paris to Port Bou on the Spanish border, which was a 12 hour journey. Going there we broke our journey with an overnight stop in Paris. We booked into a little pension near the Gard de Nord station for bed and breakfast. Our pension appeared to be the only one that wasn't a brothel in that street. Perhaps it was and we never knew about it. The room was very comfortable and clean. We visited as many sights in Paris as time allowed us, The Arc de Triomphe, Eiffel Tower, Place de la Concorde etc. I was fascinated with the place and still am. It is my most favourite city after Glasgow. I would like to spend April to September in Paris. An unfulfilled ambition alas.

The little pension that we stayed in, in Paris was near the notorious red light district of Pigalle. This was one of the most popular tourist (or should I say, whorest) attractions in 'the city of lights'. Every other doorway seemed to be a 'girlie club' with ladies of the night 'hawking their mutton' outside. Their requests for 'you want fuckie fuckie?' fell on deaf ears as we didn't want a dose of the 'clap' and having to make an embarrassing visit to the infamous clinic in Black Street in Glasgow. We crossed Paris to the Austerlitz station to get the train for Spain, having to change trains at the Spanish border town of Port Bou. We continued to our holiday destination of San Feliu which is the capital of Costa Brava. This was a delightful little place and our hotel was even better than our expectations. We enjoyed the swimming in the warm Mediterranean Sea. I hired a little boat one day and rowed out quite a distance from the shore. I got badly sunburned as I was only wearing swimming trunks. On the return to the hotel, my knees buckled from underneath me with sunstroke. I went to be feeling quite ill, but thankfully I was back to normal about 4 hours later. I've never ever went out in the sun with my shoulders uncovered since. I learnt my lesson. John and I tried to keep away from the tourists bars. We frequented the ones used by the locals, who were mostly fishermen. We went in to one such place one night, where they were having a sing song, so not being backwards about coming forward, I got up and gave a song. I received a sympathetic clap, but the manager must have liked me. He brought me over a bottle of cognac. It only cost about 6 shillings or so across there, but it was a nice gesture much appreciated. Drinking it was another thing. It nearly burnt our throats off, so we shared it with the fishermen. The price of booze was very cheap then. It cost about one shilling and sixpence for a large gin and orange, and similar drinks could get you 'blootered' for ten shillings. It amused me to go into a shop for cigarettes. There were never any on display. They were all kept under the counter. The reason being that they were all smuggled into the country from North Africa. They only had American brands 'Lucky strike, Philip Morris etc'. Horrible things but better than nothing. A great play was to pass them to you without anyone noticing. On one occasion all I could get was 20 Spanish cigarettes for the equivalent of sixpence. They had yellow paper and black tobacco. One drag was worse than being stuck in a tunnel with a steam engine for half an hour during the rush hour. I gave them to a Spaniard. My chest couldn't stand them. I went to Spain with £35 spending money and came home with £5. Changed days indeed.

Around the latter half of 1957, I went to the St Andrew's Halls one Saturday night as usual to dance. I joined the large queue and when I got about ten yards from the door, they put up the 'full' signs. Disappointed, I retired to a nearby pub to decide where to go over a pint. The alternatives were The Albert, Locarno or the Berkeley. For some reason or other, I decided to go to The Berkeley although it was my least favourite hall. In I went not particularly looking forward to it. I spotted a beautiful girl standing across the hall. I thought 'She's for me' If there is such a thing as 'love at first sight' this was it. The words of the Rogers and Hammerstein hit song came to mind

'Some enchanted evening, you may see a stranger

you may see a stranger across a crowded room

and somehow you know, you know even then

that somewhere you'll see her, again and again'

I went over and asked her to dance. We danced very well together. I asked her again a few moments later and on the third dance together I plucked up the courage and ask if she would join me for a coffee. To my delight and amazement, she agreed. I couldn't believe my good fortune. She introduced herself as Betty Heaney. I noticed a holy medal hanging from her watch strap. 'Oh Hell' I thought 'she's a Catholic' but I was so captivated by her it didn't matter, not even when she said she lived in far away Dumbarton, which normally would have put me off. We danced together for the rest of the evening getting on famously. At the end of the evening, I walked her to Charing Cross station for her train back to Dumbarton. I asked her for a date the following Saturday, she agreed. I walked home that night to Maryhill on cloud nine. I believe fate brought us together that night. Betty told me that she had arranged to meet her girlfriend that night outside the Berkeley, but her friend never turned up and she done something that she had never done before and that was to go into a dance hall alone. I had also not intended to go to The Berkeley either.

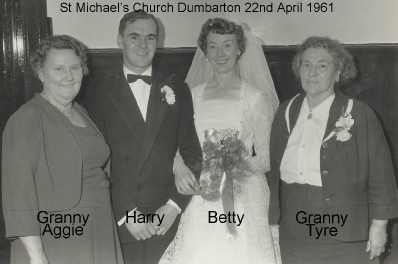

I could hardly wait for the next Saturday to come. I arranged to meet her at Charing Cross station. I went there expecting a 'dissy' a Glaswegian expression for a disappointment. What would a lovely girl like her see in someone like me? When the train arrived, there she was. We went firstly to a pub in North Street 'The Wooden Hut' no longer there. Unfortunately it got gobbled up by the motorway running through Charing Cross, tearing out the heart of that part of the city. The city planners have a lot to answer for. We then went to the cinema, got to know each other a little better and made another date. Our romance blossomed. With me working shifts on the railway it was sometimes a whole week between our dates. I used to write letters to her on these weeks pouring my heart out to her, professing my love to her. I could express my feelings better on paper than in speaking. She must have liked my letters, she kept them. I finally got invited down to Dumbarton to meet her family. Her mother and two of her sisters were there to give me the once over. Her mother Aggie was a great character. She used to mix up her words which amused me greatly. She would say things like 'Ah don't like that Arthur Askit (Askey), An askit is a headache powder. She liked 'yon senerator Kennedy'. She was a real Mrs Malaprop. Betty's father Jock was dead when I met her. I took Betty to meet my mother. Betty incidentally was the first girlfriend I ever took to my home. My mother liked her which pleased me.

1960s